This article is based on the book 'The Elephant in the Brain' by Robin Hanson and Kevin Simler. The explores self-deception and hidden motives in human behavior.A man always has two reasons for doing anything: a good reason and the real reason

- JP Morgan

The point of the book is that people don’t typically think or talk in terms of maximizing social status—or, in the case of medicine, showing conspicuous care. And yet we all instinctively act this way. In fact, we’re able to act quite skillfully and strategically, pursuing our self-interest without explicitly acknowledging it, even to ourselves.

These motives are hidden and we are not even fully conscious of them. This is odd.

Why are these motives hidden?

It’s not that we’re literally incapable of perceiving these motives within our psyches. We all know they’re there. And yet they make us uncomfortable, so we mentally flinch away.

Our brains are built to act in our self-interest while at the same time trying hard not to appear selfish in front of other people. And in order to throw others off the trail, our brains often keep “us,” our conscious minds, in the dark. The less we know of our own ugly motives, the easier it is to hide them from others.

We are not exactly 'lying' if we don't showcase our ugly motives as we are not consciously aware of them.

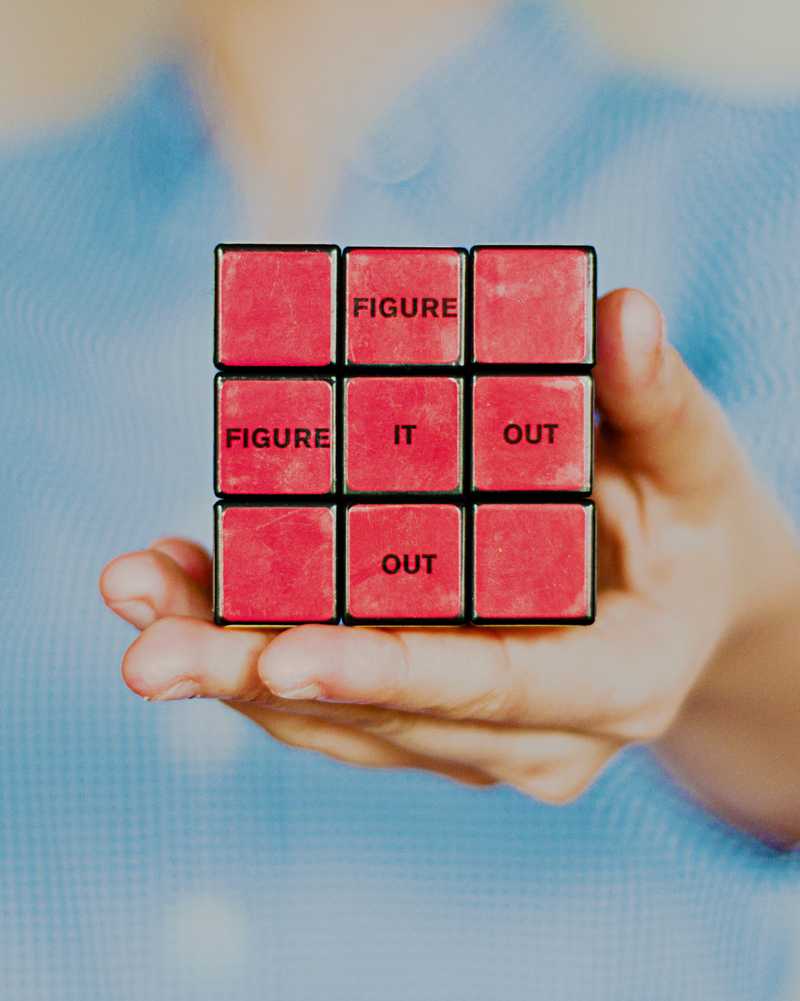

Where does the Rubik's cube fit in?

Consider why people buy environmentally friendly “green” products. Electric cars typically cost more than gas-powered ones. Conventional wisdom holds that consumers buy green goods—rather than non-green substitutes that are cheaper, more functional, or more luxurious—in order to “help the environment.”

Experimental evidence says that its not about being helpful to the environment, but its because they more expensive. They want to be seen as being helpful and they want to signal their wealth to the world. I wonder what else do humans like to signal? One of the things is intelligence

A Rubik’s Cube isn’t just a puzzle; it’s often an advertisement that its owner knows how to solve it, a skill that requires an analytical mind, not to mention a lot of practice.

I can also solve a Rubik's cube and I can confirm that it impresses at least some people. I once brought one to my school and a teacher got really impressed, even though I was being yelled at just 5 minutes before. I don't know how much of a hidden motive I had in that. It was surely there. Sometimes I just like to aspire it out and start solving it because I like to feel "cool".

We know that we have hidden motives. I admit that I do but does that mean that I should stop solving Rubik's Cubes? Certainly not.

Conclusion

First and foremost, humans are who we are, and we’ll probably remain this way for a good while, so we might as well take accurate stock of ourselves. If many of our motives are selfish, it doesn’t mean we’re unlovable; in fact, to many sensibilities, a creature’s foibles make it even more endearing.

There are certainly uses of 'The Elephant in the Brain' like:

Better Situational Awareness

It’s easy to buy into the stories other people would sell us about their motives, but like the patter of a magician, these stories are often misleading. “I’m doing this for your benefit,” says every teacher, preacher, politician, boss, and parent.

Choosing to Behave Better

Another benefit to confronting our hidden motives is that, if we choose, we can take steps to mitigate or counteract them. For example, if we notice that our charitable giving is motivated by the desire to look good and that this leads us to donate to less-helpful (but more-visible) causes, we can deliberately decide to subvert our now-not-so-hidden agenda.

Accepting 'The Elephant' in humans also doesn't mean that bad behavior is ok and its not an excuse to say 'That is what humans are' . The motive of understanding 'The Elephant in the Brain' is so that we can acknowledge our selfish motives without endorsing or glorifying them. We need not make virtues of our vices.